In places like the United States, the term “expert,” especially in legal proceedings, carries particular weight. For many, there is an inherent desire to trust the veracity of an expert by nature of the title alone. Expert implies authority, knowledge, and a comprehensiveness of subject matter based on years of study and real-world experience.

However, prosecuting attorneys, defense attorneys and judges have an obligation to question the quality of expert testimony that enters their courtroom. Failure to do so risks sullying the integrity of the court and its judicial rulings. Moreover, it muddies the waters between good science and “junk science,” and poorly reasoned verdicts (based on flawed data, flawed technology, and flawed opinions) can cause or exacerbate demonstrable physical or psychological harm to the parties involved, including decades-long prison sentences based on wrongful convictions. Flawed opinions can also result in a mistrial or having the case overturned on appeal.

Ensuring that quality of evidence is what the Daubert Standard is all about. In today's increasingly data-driven, digital world, expert opinion is an integral component to many courtroom presentations. Understanding what the Daubert Standard is and how it applies to 3D scanning equipment is critical if such expert opinion is going to be admissible in court.

It all Begins with a Lie (Detector)

It's perhaps fitting that the discussion of expert testimony in court and the history of the Daubert Standard begins with a lie. Not a lie outright — a lie detector, better known as a polygraph machine, and a judge's 1923 ruling that the evidence from such a device was inadmissible in court because the technology (and its findings) was not considered generally accepted science.

That case, Frye v. United States, established what became known as the Frye Standard, a legal precursor to Daubert. For the next half century, it came to dominate American jurisprudence when accepting or rejecting expert testimony — and expert technology — in court. Today, it remains the standard in several states, including New York, California, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Washington. Other states use modified versions of the Frye Standard, sometimes known as “Frye-plus.”

But by 1975 Frye's national dominance began to wane after the introduction of the Federal Rules of Evidence, or FRE and Article 7, dealing with opinions and expert testimony. At the heart of Article 7 reads rule 702: A witness who is qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify in the form of an opinion or otherwise if:

- The expert's scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue

- The testimony is based on sufficient facts or data

- The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

- The expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case

In the years after 1975, it was increasingly found that the Federal guidelines differed materially from the older Frye Standard. But it wasn't until 1993 that the Supreme Court case Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., reconciled this difference and established the new Daubert Standard.

The U.S. Supreme Court, echoing the language of FRE 702, said in effect, that “general acceptance” for expert testimony was no longer enough. Specific thresholds of evidence admissibility must be met, which include:

- Whether the theory or technique in question can be and has been tested

- Whether it has been subjected to peer review and publication Its known or potential error rate

- The existence and maintenance of standards controlling its operation

- Whether it has attracted widespread acceptance within a relevant scientific community

Two additional court cases in 1997 and 1999 fleshed out Daubert even more. Collectively, the rulings held that appellate courts can still review a trial court’s decision to admit or reject expert testimony and that Daubert factors can be applied to experts who are not scientists, like engineers.

Daubert for Public Safety Professionals

With the 1999 ruling, the Daubert Standard entered its modern phase. For public safety professionals and crime scene investigation this meant that engineers and those responsible for developing the latest forensic investigation equipment could testify as experts in trials.

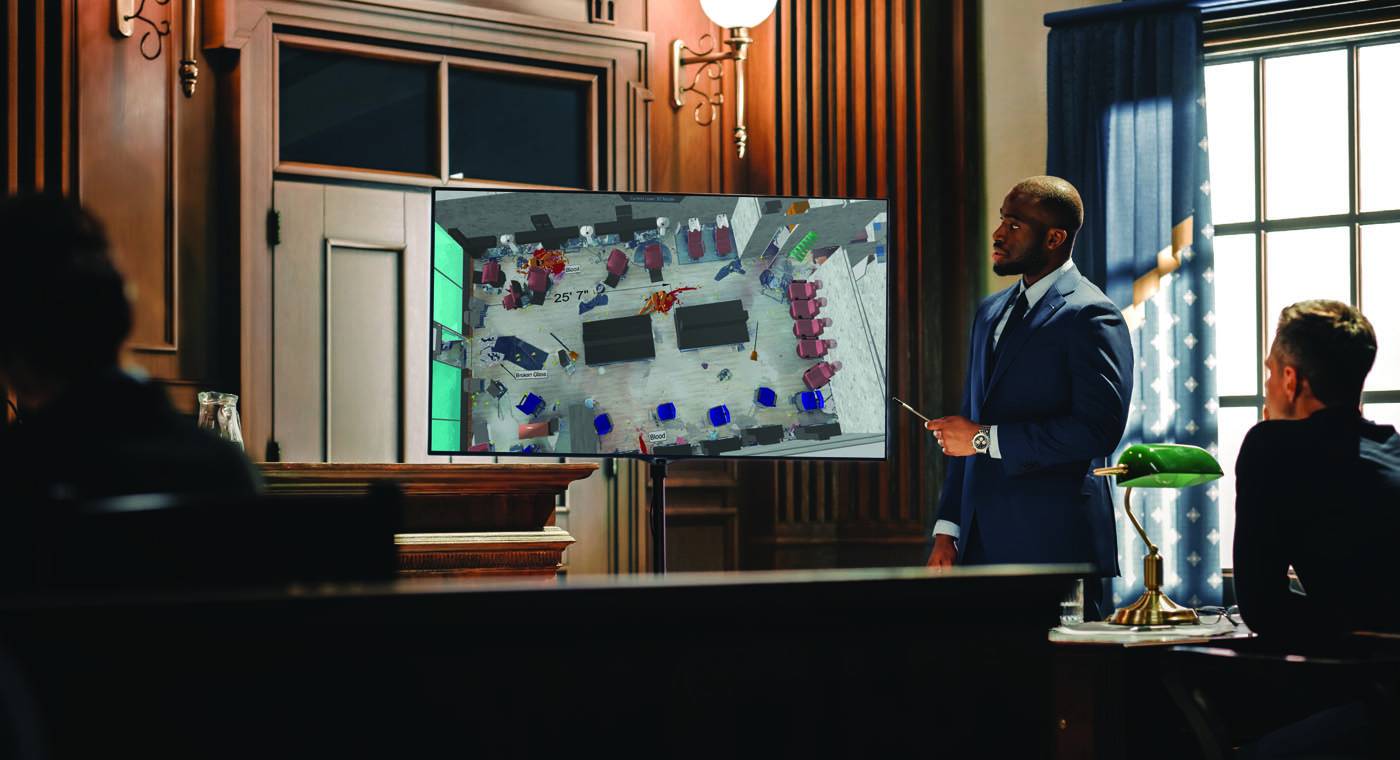

This allowance has profound implications for the laser scanning technology that FARO® Technologies and other third party providers develop. The stakes couldn't be higher: every survived Daubert challenge is a check-plus in the victory column for the industry as a whole. And as new challenges arise, a growing body of case law helps build a robust narrative that 3D laser scanning is the new standard in the world of public safety; the standard by which the crime scene evidence is collected, catalogued and shared digitally with all relevant parties. Not only that, but that it is collected with accuracy and repeatability that rivals — and by some metrics, exceeds — total stations; a statement which a standard deviation analysis confirms and whose findings were published in the journal Association for Crime Scene Reconstruction.

FARO has been involved with two recent Daubert and Daubert-related challenges, one in West Virginia in 2021 and one in Florida in early 2022. Both cases resulted in FARO winning its respective Daubert and Daubert-related motions . The Daubert-related test speaks to a motion in limine (Latin for: “motion at the start”) in which the defense sought to have certain FARO 3D scanning evidence excluded from trial. While not strictly a Daubert test, the judge in his ruling was quite clear, referencing the elements of a Daubert challenge that must be met.

“The Court finds that the technology of 3D Scanning and mapping is reliable; that it does rely upon demonstrated scientific methodology that has been subject to testing and peer-review; the techniques used by the persons who have testified as experts today are generally accepted within the community; the process involves a known error rate which was testified to as 1 millimeter at 10 meters, I believe, and a slightly higher potential error rate at 35 meters. For those reasons, the Court does find that the testimony and evidence relating to the use of 3D scanning technology is admissible under Daubert.”

The second case, the State of Florida v. William John Shutt, involves charges of second-degree murder and attempted second-degree murder. In it, a January 28, 2022 evidentiary hearing on the admissibility of FARO crime scene capture evidence with an added emphasis on the company's SCENE2Go app , 3D investigation software, which allows users to view SCENE scan projects without owning the full SCENE software, was held. Here, too, it was found that the evidence was scientifically valid and met the criteria to withstand a Daubert challenge.

For FARO and for third party providers like FARO, rulings on motions like this are encouraging news. But it's important to remember that in the U.S., the law is rarely static. Built upon the findings of lower courts in new trials, today's modern Daubert Standard may undergo a similar Frye-like change.

In the future, new admissibility requirements for evidence may need to be met, including criteria specific to 3D laser scanning. Of course, until the Daubert Standard changes and courts make new law, understanding its existing criteria is critical in the effort to overcome such a challenge. FARO, it should be noted, offers Daubert challenge legal assistance, if such support is requested at the time of a trial. But whether it's crime scene reconstruction, the location of bodies, bloodstain pattern analysis, or bullet trajectories, the same type of analysis, accuracy, and repeatability studies underpin the solid science behind all the multifaceted crime scene applications that this kind of forensic technology provides.

Final Verdict

Since their development in the 1960s, laser technology, or Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation, has come a long way. What began as a bulky, energy-hungry device with power outputs of only 1 milliwatt, has evolved into highly compact tools that are deployed across a host of industries, with public safety an established leader.

Calculating the speed at which a beam of laser light hits a target/object and the time it takes for that light to be reflected to a measuring device is at the heart of how 3D laser scanning works. From the device makers' perspective, it is settled science, decades in the making.

Nevertheless, the judicial system must continue to pursue its own due diligence on a case-by-case basis. Judges must persist in their role as expert gatekeepers to ensure that only solid science enters their courts.

In the final analysis, legal standards like Daubert, like Frye and like FRE 702 are less resembling challenges to overcome or motions to “beat,” but instead welcomed legal tools that help our rules-based, institutions-organized society (and others like it) get to the truth.

To aid public safety professionals in their work, FARO offers Daubert challenge legal assistance if such support is requested at the time of a trial.

Want to learn more about FARO’s 3D measurement devices and how we support public safety efforts worldwide?